With the pinch of a needle, cosmetic dermatologists such as Michele Green can make forehead wrinkles disappear and deep-furrowed crow’s-feet puff back out like yeasted dough. Botox is totally magic, a little unsettling, and very in demand: Green’s New York City practice has been swamped as Americans seek to give themselves a “post-pandemic” glow-up. But these days, many of her patients aren’t after eternal youth and sex appeal. When Green reviews her schedule for the week each Monday morning, she told me, “I’m just like, Oh my god.” At least a quarter of her Botox appointments are for people with a different motive entirely: They can’t stop clenching their jaw and grinding their teeth.

Across the country, patients dealing with the meddlesome condition are now turning to Botox—yes, Botox. “It’s a very popular treatment” for people who grind and clench their teeth, Lauren Goodman, a L.A.-based cosmetic nurse, told me. Bruxism, the official term encompassing both behaviors, is an involuntary action that tends to happen when people are sleeping at night, for reasons including alcohol and tobacco use, sleep apnea, and stress—perhaps why the condition has soared in the United States during the pandemic. The condition is a tolerable nuisance for many people, but the symptoms can get very real: With bruxism on the rise, dentists are reporting more chipped and cracked teeth in patients, along with jaw pain and facial soreness. In the most severe cases, patients can suffer debilitating headaches and jaw dislocation. The most common treatments, such as mouth guards and lifestyle changes, only sometimes help get rid of symptoms.

That’s what makes Botox so appealing for the recent flood of teeth grinders. Jaw injections relax the chewing muscles that clench and grind with up to 250 pounds of force—potentially relieving pain and preventing dental issues in the process. It’s not as though every teeth grinder in America is hotfooting it to their nearest Botox clinic, but the procedure seems to have blown up since the start of the pandemic. Five dentists and cosmetic experts told me they’d noticed an increase in teeth grinders and clenchers getting Botox. People who have exhausted more traditional routes are “really just committed to alleviating their pain,” said Samantha Rawdin, a prosthodontist in New York City. “If that means getting a needle to the face, so be it.”

But even if Botox has some upsides, it’s hardly the permanent, sure-thing solution that dentists and patients have long searched for. That’s been the narrative all along with bruxism: Because there are so many possible causes, treatments are an educated dice roll—and none of them is universally effective. “I don’t tell my patients I can treat them,” Gilles Lavigne, a dentistry professor at the University of Montreal, told me. “I tell them I can help them manage their condition.” So, how do we still not always know how to handle this incredibly common ailment?

Botox has been creeping onto the teeth-grinding stage since long before the pandemic. Although it has gained noticeable traction over the past few years, research on the efficacy of Botox stretches back to the late 1990s. In the years since, researchers have also discovered that the injections, which temporarily paralyze the masseter muscles responsible for grinding and clenching, can reduce the frequency and intensity of bruxism. It’s one of a slew of non-cosmetic Botox uses that have been identified since the drug hit the market in 1989: Injections also treat issues such as excessive underarm sweating, acne, and migraines.

Botox for bruxism hasn’t been FDA approved, so it’s still considered off-label—but anyone with a Botox license can legally inject a willing teeth grinder. And at least in theory, Botox has some advantages over other bruxism treatments. Night guards might prevent you from gnashing your teeth into smithereens while you sleep, but they can be ineffective at stopping the behavior and can even make it worse—especially if you have sleep apnea, Jamison Spencer, a dentist and sleep-apnea expert based in Boise, Idaho, told me. Minimally invasive regimes such as yoga, meditation, cognitive behavioral therapy, and physical therapy are hit or miss. Muscle relaxers can be helpful for some patients, but those aren’t universally popular among the dentists I spoke with, some of whom cited America’s opioid crisis as a concern.

When less invasive treatments don’t work, Botox might be “the next frontier,” Leena Palomo, a professor at New York University’s College of Dentistry, told me. Grinders and clenchers seem to be learning about the injections from a variety of sources. Rita Mizrahi, an oral surgeon in New York who offers Botox for bruxism, told me that her patients are typically referred by their regular dentists. Others discover jaw Botox in online forums such as Reddit and the beauty network RealSelf, where often anonymous discussions of the procedure abound. And some are reading mainstream-media testimonials or hearing about it from friends or family—particularly as more and more Americans embrace Botox for cosmetic purposes.

At its best, the procedure can really help certain teeth grinders: Studies have indicated that Botox can decrease pain levels. One RealSelf reviewer described trying night guards, stress relief, and cutting out caffeine before getting jaw injections. “Thank goodness for something like Botox to come along in this day and age,” they wrote four months after getting the procedure. The procedure comes with some cosmetic changes too: Grinding and clenching all night can be a workout, which might lead to enlarged chewing muscles and a square, boxy face. The injections slim the jawline for many patients, giving it “more of a V-shape,” Green said.

But Botox has some real downsides—and plenty of dentists are still hesitant to recommend it. For starters, it’s expensive and impermanent. The procedure typically costs at least $1,000; is not covered by medical or dental insurance; and usually won’t last for more than four months. “This isn’t a onetime thing and you’re good,” Mizrahi said. And like most of the other treatments available, jaw Botox attacks teeth-grinding and clenching symptoms, but not the cause. Because people still need to chew, the masseter muscle isn’t totally immobilized—meaning that patients “will just grind with less power,” Lavigne said.

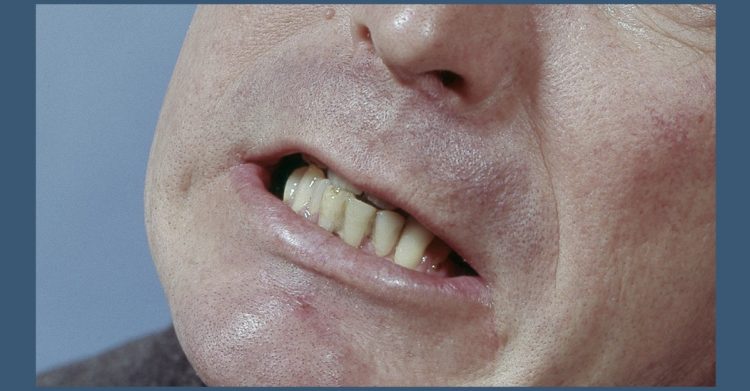

And all of the risks associated with the cosmetic use of Botox apply here too, such as bruising at the injection site, headaches, allergic reactions, and less desirable changes in facial expressions due to misplaced Botox. One RealSelf reviewer experienced no improvement in jaw pain but the unfortunate onset of a creepy grin that resembled a “chucky doll smile.” Another said that their headaches disappeared after the procedure, but so did their cheeks: “I couldn’t recognize myself in the mirror and looked like I had aged 10 years within a couple of months.”

That grinders and clenchers are more frequently turning to Botox is hardly a pure success story. Early mentions of teeth gnashing exist in the Bible, yet we still don’t really understand how to make it stop. I know firsthand how frustrating that feels. In January, after trying (and failing) to open wide enough for a crispy chicken tender, I was finally motivated to see a dentist—who gave me a night guard so I’d quit slamming my teeth together. I meditate like it’s my job, I don’t have sleep apnea or take medications of any sort, and yet I still gnaw on that hunk of plastic like it’s gristle. My jaw doesn’t lock anymore but it’s still tense most mornings. I’m priced out of getting Botox—so, like many teeth grinders, I’m stuck in medical purgatory.

Teeth grinding isn’t like a broken arm, where cause and effect are obvious and fixable. “Because the origin of [jaw] pain is not singular, you have to attack it from various modalities,” Mizrahi told me: “All the things that potentially contribute to the pain have to be addressed,” and that can involve fields far outside dentistry. Even dentists themselves aren’t always equipped with all the information: “We get virtually no bruxism education” in dental school, Spencer, the sleep-apnea researcher from Idaho, said.

With all these roadblocks, many patients never find out why they’re clenching or grinding, says Alan Glaros, an emeritus professor of dentistry at the University of Missouri at Kansas City, who’s been researching the issue for more than 40 years. That’s partially because it’s a difficult problem to not only treat, but also study. Bruxism’s many causes intersect “a lot of disciplines,” such as dentistry, sleep health, and psychology, which muddies the research process. Each field is studying the behavior, but the results will only ever tell part of the story. “People act as if this is all solved, but it’s not,” Glaros told me.

So for now, mouth guards, meditation, and Botox are what we have. The treatment, in all likelihood, isn’t going anywhere. “As people get to know others who have responded well, I predict that we’re going to see an uptick,” Palomo said. Grinders and clenchers will keep chomping on their plastic night guards or forking up thousands of dollars a year for temporary injections, all in a maybe-successful attempt to quell their pain. If only Botox could banish bruxism like it does stubborn wrinkles.

Source by www.theatlantic.com